Vitebsk Virality

It’s rare that anything from Vitebsk goes viral, these days. Yet in the last week an extraordinary and all too rare collaboration between the worlds of fine art and football, went viral on social media, prompting comment from art portals on the kit launch of a mid-table Belarusian top flight football club.

FC Vitebsk launched a commemorative shirt featuring Lazar Markovich’s (“El Lissitzky”, 1890-1941) iconic Russian Civil War poster, Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge. This year is one hundred years since the emergence of the avant-garde artistic formation UNOVIS at Vitebsk’s art school, then under the direction of Marc Chagall (1887-1985) and including Kazimir Malevich (1879-1935) on the staff as one of it’s more popular teachers. For a brief moment between it’s foundation in 1918 and c.1922, Vitebsk featured one of the most advanced and open art schools, and most radical curriculums, anywhere in the world. The shirt also celebrates one hundred and thirty years since the birth of El Lissitzky in 1890, and the formation of Vitebsk’s football club in 1960.

Whilst Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge, in time, came to symbolise the radical break in visual art that happened in Russia in the lead up to the First World War and the revolutionary period, still comparatively little is known about the town and the art school where the work originated, in the English-speaking world.

It’s easy to be cynical about football club shirt launches. Since the early 1990s football clubs have sought to get supporters to part for ever larger chunks of cash for pieces of branded polyester sold at a huge mark-up; moodily back-lit fashion-shoot type events featuring famous players modelling the latest shirt are humdrum events now, that do little to stop the jaded twitter user scrolling past indifferently. But this collaboration between Vitebsk Football Club, the local history museum, and the Centre of Belarusian-Jewish Cultural Heritage, has produced quite a unique shirt. Unusually for Belarusian club shirts, it’s also easy to buy: you can source it directly from Moscow’s Nothing Ordinary online store.

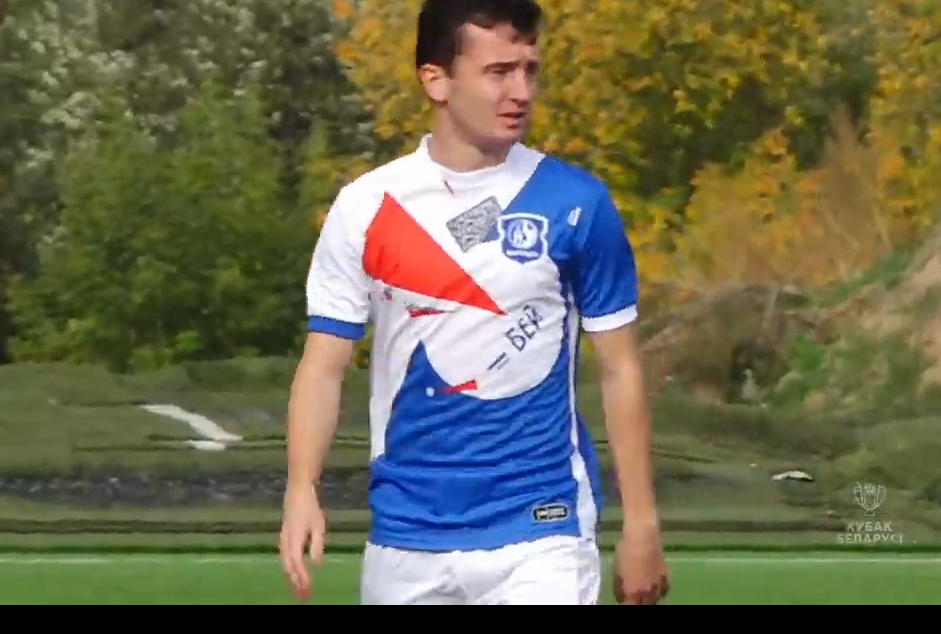

The initiator of the project is Vitebsk centre-back Daniil Chalov, a mainstay of the club’s defence this season. His comment on the project was really insightful:

“There is a fine line where art and football merge. Both are a game with a whole life hidden inside. Both of them cause strong emotions and feelings, due to which you can escape from the gray everyday life and feel alive. The depth of feelings that people of art and athletes try to convey with the help of their work is, first of all, a huge work, years of patience. After all, to achieve results and find a response in the hearts of people, you need to learn the subtleties of your work for many years and be in a constant process of improvement”

Chalov’s comments are the basis for this article. For a long time (loosely) I have been trying to pull together various fragments on the crossovers between art and football and will one day produce a book about it. For now, though, this will be about this new Vitebsk fragment, which so captured people’s imaginations this week.

Yehuda Pen to UNOVIS : Vitebsk & Modern Art

At the turn of the twentieth century provincial Vitebsk was part of the Pale of Settlement, the territory reserved for the Jewish population in Tsarist Russia. This territory covered most of the Western districts of the Tsar’s empire and included all of present-day Belarus. The right of Jewish citizens to live outwith the Pale of Settlement and to engage in certain sectors of the economy was heavily restricted, and within this territory life was very difficult for many. Another Belarusian-Jewish artist, Chaim Soutine, left Smilyavichy, a village near to Minsk, as a young man, for Paris, and never returned; his career and life was marked by the pitiless and unrelenting poverty he suffered in the Pale of Settlement.

Vitebsk was known at the beginning of the twentieth century as a city of craftsmen; the organisation and development of modern art was driven by the city’s Jewish population.

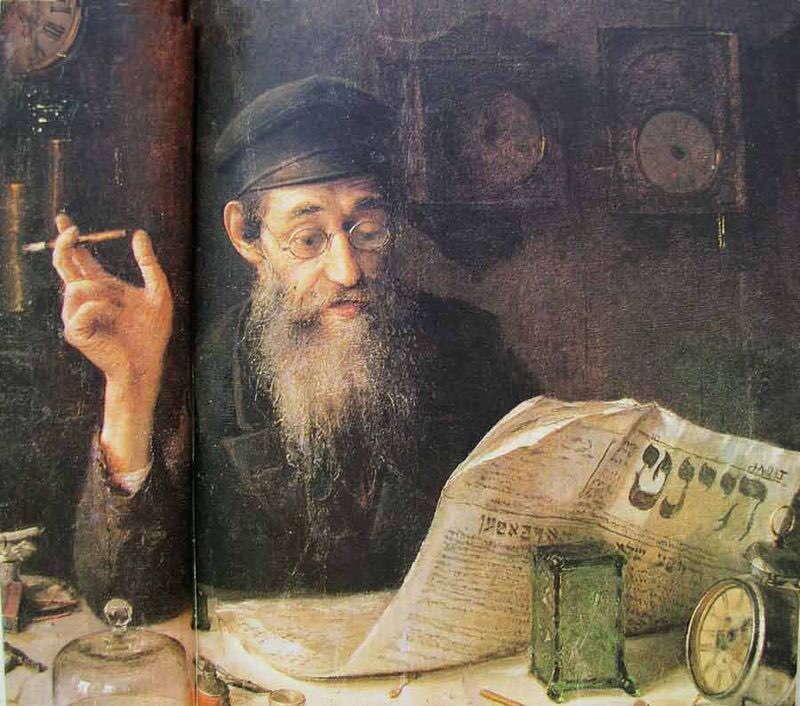

The first noted city painter and tutor of young artists was the much loved Yehuda Pen (1854-1937), a realist and humanist portrayer of Jewish life both in Tsarist and later, Soviet times. It is astonishing to note how far the visual arts travelled in Vitebsk in just five years, if we compare Pen’s Clockmaker of 1914, with El Lissitzky’s poster made just five years later.

In retrospect, Pen’s portrait functions as an image of a life that was fast disappearing. Enjoying a moment’s peace from his work, the clockmaker smokes and studies a local newspaper in Yiddish. With sympathy and verve, Pen uses the tools of an experienced portraitist, using dramatic props (finished and unfinished clocks; tools; artificial light; clothes and the newspaper to give us a precise understanding of who this character is, and of his role and position in society. It was this kind of portraiture that Pen tried to impart on those who came to study with him at his house-cum-studio on Gogol Street in Vitebsk, a building long since demolished. When this work was finished, few could have foreseen that Marc Chagall-Pen’s most promising students- would already have overseen the visual components of a street festival in Vitebsk, celebrating a year of the Bolshevik revolution, and would in January 1919 be appointed director of the Vitebsk people’s art school.

Vitebsk in the period 1919-24 shuttled between various territories; part of Belarus, part of a joint Lithuanian-Belarusian Soviet republic, then part of the Russian Soviet Republic, then, finally, settled as part of Belarusian territory in 1924, where it remains to this day. This period coincided exactly with the most revolutionary years of the art school under the direction of Chagall and, after his departure in late 1920, Vera Ermolaevna. The people’s art school was open to all, regardless of ability, who wished to study there; it retained the intimate atmosphere of a private atelier like Pen’s, with the formal and theoretical rigour of a curriculum designed by some of Russia’s leading contemporary artists. Moreover, in revolutionary times, it was the role of those employed at the art school to not only show but involve their fellow citizens in the latest developments in modern art.

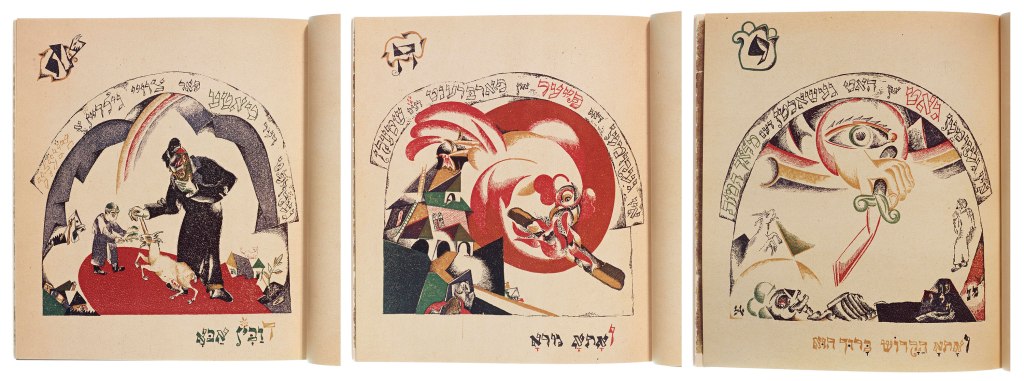

It was in this context that El Lissitzky created his now very familiar poster Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge. Whilst the image can be read literally, as the Communist Reds attacking and forcing back the reactionary forces of the White armies, there is also a geometric ambiguity about the piece; no one new whether the attempt at making a new society of equals would last or be crushed, at this period. The work functions easily as visual propaganda for an audience that was largely illiterate before 1917; yet, in spite of the immediate and urgent revolutionary context in which it was made, the piece also leans heavily on Russian and Jewish antecedents. the work relates in part to the traditions of the lubok, a type of woodblock poster printing that enabled social, political and satirical messages to be conveyed to audiences who had trouble reading; in the same year as this poster was made, Lissitzky, who was fascinated by Jewish material and religious cultures throughout his life, had made a series of woodblock prints in an illustrated book on the subject of Had Gaya (“One Little Goat”), a song traditionally sung at the end of the Jewish Passover festival. That a much more traditional set of images such as these wonderful images shown below, showed the versatility and range of El Lissitzky’s practice during his brief time in Vitebsk. Traditional religious identifications and the role that Jewish people might play in a future Soviet republic sat alongside a desire to promote the Bolshevik cause to the people.

The foundation of UNOVIS, a Russian acronym meaning “Champions of the New Art”, on Valentine’s Day 1920, seemed set to place Vitebsk at the very forefront of developments in modern art in the period. UNOVIS was open to all and was part art groups, part exhibiting association, part para-political formation aiming to internationalise the ideas of it’s main theorist, Kazimir Malevich. Malevich had begun working on Suprematism as an idea in late 1913 and by 1920 he had developed it fully into a series of axioms, paradigms and (impenetrable) theoretical tracts. Malevich and El Lissitzky, together with Vera Ermolaevna, collaborated on a production of Matyushin, Kruchonykh and Khlebnikov’s Futurist Opera Victory over the Sun whilst the city of Vitebsk itself briefly became envisaged as a gallery and exhibiting space for UNOVIS inspired works.

Alongside this frantic pace of activity and production, Malevich’s Suprematist manifesto and a UNOVIS almanac, with the cover designed by El Lissitzky, appeared. Suprematism, in short, sought to turn it’s back on the object in art, instead to provide implifed, abstract visual ciphers relating to “pure emotion” and “pure thought” in art. Little surprise that sucg rarefied and specialist ideas didn’t long survive the rise to power of Josef Stalin, after Lenin’s death in 1924. By the middle 1920s Malevich was again painting figuratively, under heavy pressure from the authorities.

In parallel to these developments, elsewhere in Vitebsk the literary theorist and philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin was developing his theory of the carnivalesque, based in part on his experiences of the revolutionary crowd during this period. Sadly, history shows us that this brief moment of Vitebsk functioning almost as a kind of mini-Vienna, as a magnet for intellectuals and artists and an extraordinary free laboratory of creative experimentation, was short-lived. By 1922, all of the main actors- Chagall, El Lissitzky, Malevich- had dispersed, and only one cohort who had worked through Malevich’s radical UNOVIS curriculum graduated before the programme was closed and the art school brought “under control” along much more traditional lines.

Intersections between Football and Art

It really is hard to escape from football these days. I actually feel sorry for people who are indifferent to, or actively dislike, the sport. It seems hard to credit now, but thirty years ago, the expression of an interest in football by an “art” person was met with suspicion, or incredulity. These were the days when hooliganism in England, and on the continent, was rife, and Mrs Thatcher, an avowed disliker of the game, was proposing the introduction of ID cards at football matches.

The interactions between contemporary art in Scotland, and football, rarely attract such attention, simply because they slip beneath the radar of most. The artists associated with the “Glasgow Miracle” period of the early 90s had a regular kick about on a blaes pitch in Cowcaddens most Saturdays. (for non-Scottish readers; blaes is a kind of red sharp-edged shale, a common material for bone-hard pitches in Central Scotland, on which only the insane and the nerveless can perform a sliding tackle, and a dive can shred the goalkeeper’s jersey).

Two of those artists, Douglas Gordon and Roderick Buchanan, have gone on to produce significant bodies of football-related work; Buchanan, in his photographs of himself, friends and amateur wearing largely Milan jerseys; Gordon, in his epic film Zidane, first shown in Edinburgh in 2006-7. Graham Fagen, Scotland’s representative in Venice in 2015, was also a participant in these, even if he hasn’t made work related to the sport. More recently, some small circulation niche publications- fanzines and periodicals- have sought to examine this troubled relationship in a more systematic way, through artworks and essays.

However, the very ubiquity of the sport these days mean that artists intervening in this area can often meet with indifference, if not hostility. Buchanan’s work was unique fifteen years ago; Gordon has always strongly located part of his practice and artistic personality on his interest in the game. Despite these precedents, for some in the art world, there may be a questioning of sport as a “proper” subject; indeed, the term “sporting art” connotes images of ghastly, lumpy paintings of horses, greyhounds and terriers. From many in the world of football, the relevance of art to the production and consumption of the game seems at best tenuous, at worst downright unwelcome.

I think this is why the Vitebsk jersey and Daniil Chalov’s comments are so interesting. There are actually a significant subset of footballers with a strong interest in and commitment to contemporary art, some as collectors and consumers, others as producers. Pat Nevin, the diminutive Glaswegian winger-turned broadcaster, and ex-England international Graeme Le Saux, were two examples from the turn of the century who spoke regularly and often about art and contemporary music. The much-travelled Welsh international goalkeeper Owain Fôn Williams, currently playing for Dunfermline Athletic, turns out portraits related to his background in slate-mining North Wales, in between training and matches.

But it’s not just these individual crossovers that matter. Chalov’s project opens out much more fundamental intersections between art and football in terms of process. Cristiano Ronaldo and Lionel Messi, the great individual rivalry in international football for the last generation and more, have dominated the sport in such record-breaking fashion not just through athleticism and unquenchable ambition, but in two other ways; a relentless desire to get better through training and practice, and a quite astonishing intelligence. For those who like to dismiss footballers as stupid, that may seem a surprising statement.

The intelligence we are talking about here is an ability to read pattern and space, to anticipate how a game will develop three or four moves ahead, instinctively, and how to benefit the team as a result. This kind of spatial awareness and pattern recognition is a quality these world class players have in common with the very best contemporary artists. As is, dare I say it, the selfish desire to put the sport above everything else in a desire to improve, to the exclusion of all other things. The obsessive work rate and desire for constant success, a demand to continue improving and to have largely forgotten titles and cups the day after, demonstrated in, say, the career of Sir Alex Ferguson or Arsène Wenger would be recognised by many curators and directors who have risen to the top jobs in the global art world.

There are many more parallels that we can draw. Most saddeningly, perhaps, is the high attrition rate of those who show talent for football or visual art as a teenager who are subsequently unable to progress to a professional life, beyond either the training or the art academy. English Premiership clubs are now battling one another to sign nine and ten year old children, who then develop through their academy system; the number of young people who make it through this and into a meaningful career in the professional game is vanishingly small. The parallels with art schools and the art world are obvious.

Another obvious crossover is in the debate that spans both football and visual art; talent versus hard work. When the Royal Academy was formed in the 1760s, the discourses of it’s first president, Sir Joshua Reynolds, focused on the need to work hard; that there was no skill or aptitude that could not be improved, however naturally talented the individual may be. Reynolds had little patience for notions of ‘genius” or “divine talent”. It’s not hard to extend this debate into football. Football supporters- and football history- has been remarkably indulgent of abundantly talented mavericks with manifest character flaws; Hughie Gallacher; Dragoslav Šekularac (a Yugoslav footballer from the 60s whose nicknames included “The Artist” and “The Romantic”); Jim Baxter; George Best; Eric Cantona. An overabundance of talent can be as poisonous to a footballing career as it can be to an artistic one. If it all just comes so easily, why bother training?

There are plenty of characters like that in lower league football in Scotland and England now; players who would really be playing at a much higher level but for whatever reason- lack of application, bad luck, a lack of awareness of their own ability, an injury at precisely the wrong moment- find themselves unable to reach the levels their ability suggested they should have done. In art, the likes of an Augustus John, Nina Hamnett, and thousands of abundantly talented first class degrees lost to common memory, are a direct parallel to these types of footballers.

To return to the example of Vitebsk, it’s easy to see the brief moment of UNOVIS as a great football squad coming together and breaking up. Pen, the distant mentor and supporter, at the beginning; Chagall as a genius player-manager whose relationship with his star player, Malevich, broke down irretrievably in bitterness and acrimony; Lissitzky the grafter and producer, who would later move and achieve much bigger fame abroad before returning to Russia; it’s not a cheap parallel to apply these kinds of relationships in a football context. Football as a sport is intensely personal, with success in the game depending on the ability of a coach to shape friendships and minimise interpersonal disputes and dislikes as much as possible in the pursuit of a commonly authored success. You certainly wouldn’t have to look far within the stories surrounding the contemporary game to find very similar tales to those of the Vitebsk art world a century ago.

There are parallels in the ways that football and art are consumed in normal times, too. Writing about both has undergone a fundamental revolution in the last twenty years. The days of the old chummy talking head journos have gone; only a few of the names whose writing on the sport approached literary standard (Brian Glanville, Hugh McIlvanney) are still read seriously.

In Belarus, the closest there is to a high-quality journalist like McIlvanney is the TV and newspaper personality Nikolai Khodasevich, a man with his own telegram channel and whose weekly columns in the TUT.BY portal (@goalsby) on twitter, revealing very profound insights into the game, are amongst the best football writing anywhere at present. As with all great football journalists, Khodasevich combines a lucid, sharp-sighted passion for the game with personal drama (his on-going dispute with the stern disciplinarian coach of Dinamo Minsk, Leonid Kuchuk, has been one of the most entertaining features of this Belarusian football season).

The changes and mutation in football journalism have been mirrored by those in art criticism. Print journalism, which used to have in-house full time cultural critics, now rarely pay to employ such folk who are now invariably freelance and with a patreon or youtube channel to supplement any income from journalistic endeavours. Newspapers do still print cultural content, but often it is simply a cut and paste of a press release, or printing an article done for free by a curator or writer who have their own agendas for not taking a fee. The advent of social media and the development of digital culture have seen the specialist journalist pushed well down the obsolete road of the typist and the tail-gunner. Just as, with a bit of knowledge and an internet connection, anyone can write about football these days of they wish to, so too anyone with motivation and interest can open up debate on contemporary art. People will listen if you keep doing it well.

Belarusian Football as a Lifeline

The COVID-19 crisis has also united the seemingly diametrically opposed worlds of the creative arts and football. The highly infectious dynamics of the virus have scuppered audiences for live art. Whilst galleries have re-opened under heavy social distancing manners, helped in keeping the doors open by varied emergency funding packages, the cinema and the theatre, which do not have static exhibits to show, are facing a real existential crisis. This is before we get to the plight of precarious, freelance art workers who have simply fallen through the cracks in creative safety nets designed with the needs of institutions in mind.

Football has been through a similar terrible time in the UK, with no crowds permitted and the sport having desperately to try alternative funding models through live streaming and the good will of owners and fans putting their hands in their pockets to ensure their club survives the period of confinement we are all living through. Except if you are in Belarus.

The politics and reasons for Belarusian football continuing whilst everywhere else in the global game shut down, are for another article on probably another forum. Suffice it to say that the Belarusian league, shown free on youtube every weekend, has been a lifeline for fans around the world whose principal pleasure on a Saturday afternoon was so rudely and suddenly stopped in early March. The league is of a pretty good standard at the top and is similar to many other smaller leagues; a mixture of home grown talent developing alongside emerging global talents who pop in to play in the Belarusian top flight for one or two seasons as a means of either kick-starting a stalled career or raising a profile in a European league. The Belarusian league has gained an unprecedented amount of exposure this season and has a large online following based in the UK; this has thinned out a little recently with the English and Scottish top flights returning, and also with some fans feeling uncomfortable watching football in the context of an ongoing brutal and violent crackdown on anti-government protests in Belarus at present.

Vitebsk are quite a typical outfit at this level; a mixture of Belarusians, Russians, Moldovans, Ukrainians and Brazilians. Managed by the garrulous Sergei Yasinsky, who has been around Vitebsk football since his career as a player began in the early 1980s, they have had a reasonable if unspectacular season. Turnover of players in this league is quite high. Two of Vitebsk’s better players, the talented but unpredictable Brazilian forward Diego Santos, and Moldovan international Ion Nicolaescu, have recently left. Santos featured in the jersey photoshoot but never actually wore it in anger, leaving for the country’s richest club, Shahktyor Soligorsk. The profile of player in Vitebsk’s squad is either an established local (captain Artem Skitaw), players coming to the end of their career (Ukrainian Anton Matveenko), or players re-building after hitting difficulties through injury or bad luck. Daniil Chalov himself is a former Russian under-21 player, and had some time out of the game after leaving his last club, Shinnik Yaroslavl, but has now successfully re-built his career in Vitebsk.

For a while this campaign it looked as though Vitebsk may finish in the top four. They had a great run earlier in the season, with Diego Santos and Nicolaescu prominent, losing only once in twelve matches, with crowds growing rapidly. They proved themselves a match for even the best teams in the league, beating reigning champions Dinamo Brest, and battling back in a thrilling performance to draw 2-2 with Belarus’ serial champions BATE Borisov; a game they had been 0-2 behind in until relatively late on. Since the end of July, however, the side have struggled, gaining just two points in their last six games, and tumbling down the league table. The Belarusian cup, therefore, in which the El Lissitzky jerseys made their debut, was their last chance to try and win something.

One thing that can’t be controlled, sadly, is the internet. The stream of the game- which was either shut off as a result of the depressingly regular internet shut-downs owing to today’s protests in Minsk, or because of poor equipment- lasted all of three minutes. It was enough to get some good screen shots though of Daniil Chalov’s unique shirt on the field of play. In the end, Vitebsk won 1-0 thanks to a goal from Ruslan Teverov, who has assumed the striking duties after the departures of Nicoleascu and Santos.

The crossovers between art and football, in how they are practiced and consumed, are much more than may first meet the eye. I am very grateful to Daniil Chalov, Vitebsk FC and the shrt designers for helping me try and piece together some half formed thoughts which have been bouncing around my mind ever since lockdown. And, when the lockdown finally ends- whenever that may be- Vitebsk’s museums, streets and football club, which I have spent so much time in the last few months thinking and reading about- will be one of the first cities on my itinerary to visit.

Reading

Aleksandra Shatskikh, Vitebsk : The Life of Art, Yale, New Haven & London, 2007

Aleksandra Shatskikh, UNOVIS : Epicentre of a New World (1992)

More on UNOVIS on monoskop.org

FC Vitebsk- @fc.vitebsk.by

Belarus FA- @belarusff

Other

Buy El Lissitzky-inspired shirt from Nothing Ordinary webshop

Excellent article on visiting Vitebsk from 34travel.me

Don’t expect my book on football and contemporary art before 2023, incidentally. I’m working on it.