In Aberdeen, recently, a young Montenegrin footballer has been in the news quite a bit. Slobodan Rubežić, although born in Belgrade, qualifies for Montenegro through his mother, who was born in Nikšić. Rubežić, a towering and uncompromising centre back, has become a firm fan favourite at Pittodrie stadium already through his whole-hearted approach and sometimes erratic performances.

In the last game before the recent international break, a full throated challenge left Glasgow Celtic’s Japanese star Kyogo Furuhashi knocked-out cold; debate was intense for a couple of days on whether the young defender should have been sent off by the referee; legendary former Aberdeen captain Willie Miller, who played in the same position back in the 1970s and 1980s, wondered out loud at the new signing’s perceived recklessness. Rubežić seems absolutely fearless, but the general view is that the player has yet to balance that with fine judgement.

Emerging footballers are sometimes spoken about in the same way as emerging artists; their potential causes excitement, they (either for their work or signature) are bought and sold several times over; their exploits and where they might go next are often the topic of intense discussion. The emergence of Rubežić as a potential cult hero at Aberdeen FC is timely, as I had the good fortune last month to be invited to see the exhbition Pravi San Velikih Prijatelja (The True Dream of Great Friends) at the National Museum of Montenegro, in Cetinje, which dealt extensively with the history of football, and its treatment in art and by artists.

Montenegro has a population of 620,000 or so, a little bit less than that of Glasgow, but the small republic has the profile of a much larger country in terms of its footballing history. Five Montenegrins were in the famous Yugoslav team that won the World Youth Cup in Chile in 1987; it is one of the great what ifs of footballing history, as to how that team would have fared has Yugoslavia held together rather than being ripped apart in the nineties. My suspicion is that that team would have dominated European football, and perhaps would have had a very good chance of success at the American and France World Cups of 1994 and 1998. That team’s goalkeeper, Dragoje Leković, who started out at Budućnost Titograd, later won a Scottish Cup in 1997, with Kilmarnock.

Sensitively curated by Ana Pavlović-Ivanović and Slobodan Vušurović, the exhbition relied not just on museum collections but also crowdsourced footballing memorabilia and curiosities from around Montenegro. One of the strenghts of the exhibition was the way in which it focused on the small community clubs as well as the bigger names of Montenegrin football, as well as important sections on the emerging womens’ game in the country, and the history of childrens’ football; the relentless conveyor belt of talent that keeps the game moving along from generation to generation, in the same way that art high schools and academies keep replenishing the art world. Here is another point of unlikely comparison between art and football. Only a small percentage of the youngsters going through English premier league academies will “make it” at the top level of football; the others play lower down the pyramid, or recreationally, or even give up the game altogether. The percentage of young people going through art school making it professionally as artists, from academies, is not so much different.

The premise of the show was the unusual link between the local football club, FK Lovćen Cetinje, and visual art. The club is the oldest in Montenegro, founded in 1913 by one of Montenegro’s best painters, Milo Milunović, and his brother, Luka. The brothers Milunović has been very taken with what they had seen of football whilst studying in Italy, and brought it home with them to Montenegro, naming the country’s first club after a local mountain.

Although the club didn’t start playing regularly until the early 1920s, in the new Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (Yugoslavia), it is widely recognised as a pioneer of football in the region. A plaque in Cetinje town centre commemorates the Milunović brothers on the site of their old studio, and recognises their contribution to local football as much as art.

Lovćen are still an important local institution, serial Montenegrin champions between the wars, and significant in the early years of socialism after 1945. The club is currently in the Montenegrin second tier, trying to finish an impressive new stadium and hoping for promotion to the Premier League.

The curators used local artists very deftly in the exhibition. It is no surprise to see the work of Uroš Djurić, a Serbian artist who has been consumingly obsessed with football all his life, often commenting on the deep overlaps between the lives of the footballer and the artist. Djurić himself played for a Serbian artists’ team in Belgrade in 2006 against their Scottish counterparts, featuring Roddy Buchanan and Nuno Sacramento, amongst others. However, a long running strand of his work has been working with football teams all over Europe, and posing with them as a “twelfth man” in a team photo.

The series, entitled Populist Project : God Loves the Dreams of Serbian Artists features the artist posing with Lovćen’s current first team. These projects, which as Djurić explained, started many years ago with Sturm Graz in Austria, have taken in many other football teams and require a process of careful negotiation and explanation- firstly to convince club officials and the coach that the image is not a distracting waste of time, and then to explain to the players what the purpose of the photo is, and a mutual understanding about their briefly overlapping lives. It is an ongoing relational project and a rare direct conversation between the worlds of art and football. Alongside Djurić’s work is an interesting early video piece by Natalija Vujošević, an intense, slowed-down video featuring Zinedine Zidane’s clinical late penalty for France against Portugal in the close semi-final of Euro 2000; and sensitive and playful two dimensional work by Jelena Tomašević and Tadija Janičić.

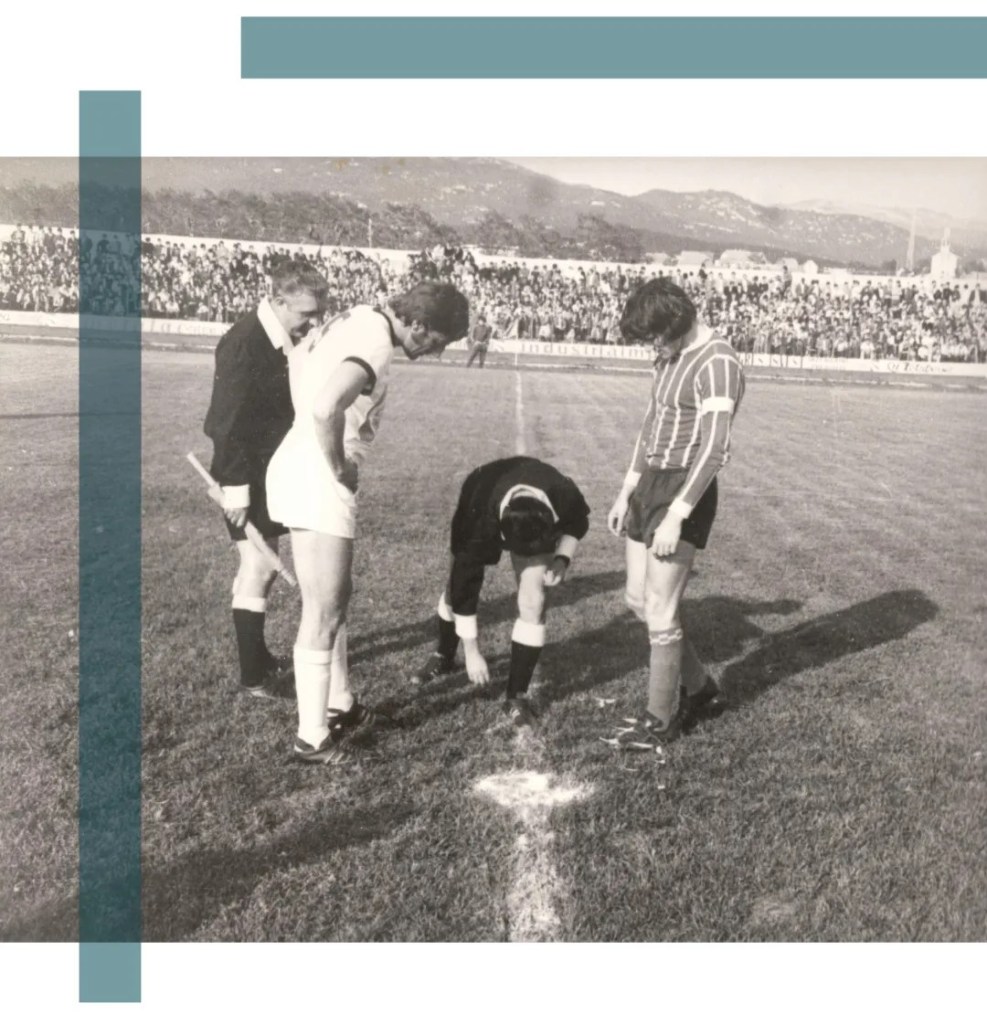

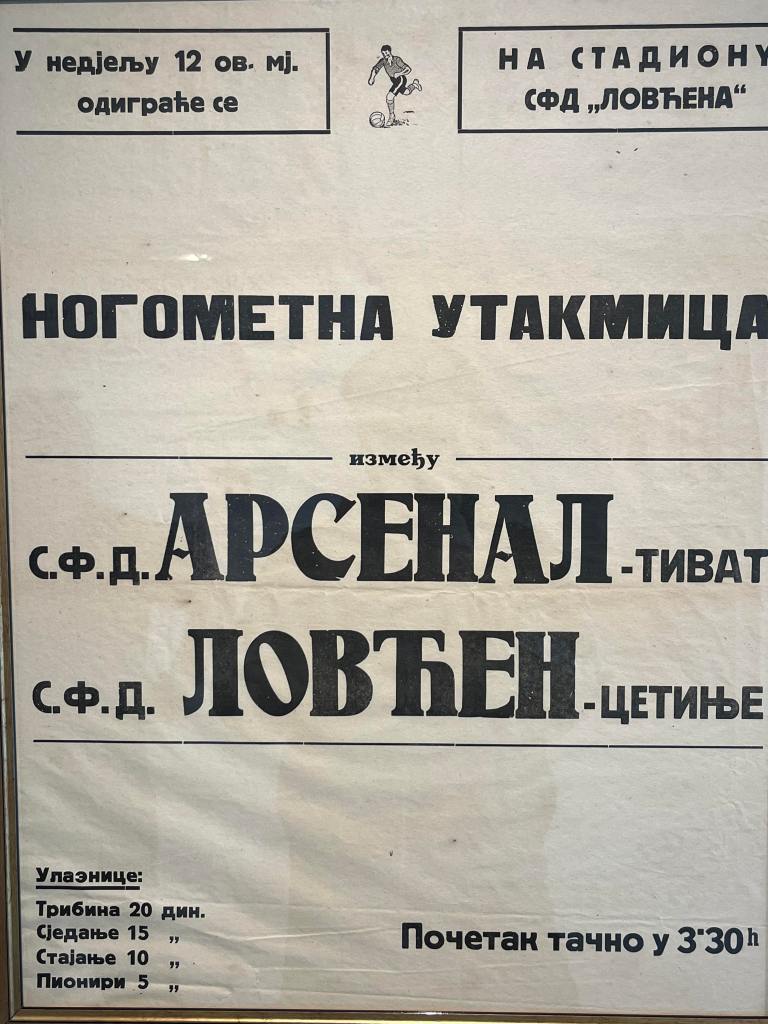

The show was also interesting for the human stories it related and the ways in which the visitor was invited to consider the artefacts and relics of football history as art. There was an inter-war poster of a game between Arsenal Tivat and Lovćen; an early football boot, presented with a complete back-story in the manner of a ready-made; the remarkable abstract badge of one of the country’s biggest clubs, Sutjeska Nikšić, named in 1945 after the partisan battle of Sutjeska in which many of their first team players perished. And, I’m sure the curators would have had more than a few sleepless nights at having such valuable shirts on display – the trade in old and significant football shirts is huge. Who knows, for example, the auction value of Dejan Savičević’s AC Milan shirt, let alone Predrag Mijatović’s Real Madrid shirt, worn when the Montenegrin striker’s goal against Juventus reclaimed the Champion’s League title for them, in 1998, after a long hiatus.

It can be hard to perceive the aesthetic side of football at the lower and grassroots level; even the keenest visual imagination may struggle in playing out a goal-less draw in February, in horizontal sleet. However two of my favourite exhibits were from just this level- a team photo of “Komovi” Andrijevica, a group of guys standing in front of a goal and a dramatic mountainscape behind, illustrating the close bonds of a team and a desire to play for the pride of your local village which motivates so many lower level players and club officials; it somehow reminded me of many Scottish junior team groups from years past. Developing that point, the second video piece, interviewing the owners of FK Zabjelo Podgorica, a grassroots club which like local galleries is motivated more by the community of players and fans of all levels and backgrounds, and the social benefits and ties of a football club, rather than results, necessarily.

What was left implicit, and could have been teased out a little more, was the subject of intelligence. Both artists and footballers are preceived as either not being intelligent, or certainly possessing a different sort of intelligence. This is a comparison that always frustrates me hugely. Artists and footballers may not be academically intelligent, sure, but then they don’t need to be. It struck me that a cross over between the intelligence of artist and footballer is in spatial awareness and pattern prediction.

An elite level footballer- an Mbappé or Messi- can see a game pattern developing five or six passes in advance, and seems to know instinctinvely where they have to be on the park, in order to maximise their chances of scoring or setting up a chance for another. In the same way a painter organising and setting up a canvas or in placing a particular work can often see patterns or be spatially aware in a way simply beyond that of the non-artist. Both art and football also require long, lonely hours of dedicated practice; either in the artist studio or alone after a training session with the rest of the team. Both discourses are full of stories of maverick talents who seem to be able to make art or play the game with little if any practice; these figures also tend to end up frustrated and unfulfilled, almost as though there can be such a thing as too much natural talent. For every successful footballer there are a dozen others who could have been just as good if not better; sure, luck and injuries can play a part, but often it is simply a matter of failing to work hard enough on pre-existing talent, or lacking the monomaniac dedication that is required to succeed.

This was an exhibition that took some courage to mount in the context of Montenegro. Whilst in Scotland our national obsession with football- our local clubs and national side- sees artists at very least paying lip service to the game’s existence, with bodies of work and whole magazines / galleries devoted to the inter-relationship between art and football, in the context of Montenegro the interaction between art and sport if perhaps much less well defined and discussed. This show, offering a judicious mix of football history, artefacts and visual art, left the viewer with much to ponder on and think about after the joy of encountering so many new things had faded. And, in many ways, it was the best of exhibition experiences, in that it felt like the beginning of a fascinating conversation, rather than the last word. A future game between Montenegrin artists and the Scottish artists team in Cetinje is a quite a prospect which is being discussed.

Until then, there’s Slobodan Rubežić. The young man apparently was involved in another controversial challenge in his country’s home win over Lithuania, and scored his first international goal this evening as this article was being written, unfortunately in a losing battle away with group leaders Hungary. After several years in the doldrums the current Montenegrin team is showing signs of a recovery, with a good mix of experience (captain Stevo Jovetić and Stevan Savić of Atletico Madrid) and exciting emerging talents, the best of which is Lecce striker Nikola Krstović, who has started his first season in Serie A very impressively. Rubežić looks as though he will have an important part to play in the future of both his current club and country.

Thanks to Narodni Muzej Crne Gore for inviting me to see the show and to give a talk on it, and to Gray’s School of Art, RGU, for supporting the trip. Pravi San Velikih Prijatelja ran at Narodni Muzej Crne Gore, Cetinje, from 13th September until 25th October 2023.